Consent

1 Consent? - What? Why?

Do they want to have sex with me?

Welcome to our brand-new sex ed course on consent!

In the following pages, you will not only find answers to the questions above, you will also learn how to understand your partner better.

This course helps you to be even more respectful and loving with your partner. In other words, you will learn how to have better sex.

Boring topic?Surely not!

Watch this short clip in the metro in hip Berlin to get yourself ready for our amazing course:

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

Now click on the button on the right to get an overview of what you will learn in the course.

(Illustration by Elyssa Rider)

Feel it! Pulling someone closer can be a way to express consent.

2 Outline of the course

The course structure is dead simple.

1. What is consent?

Here you will get a better understanding of what consent actually means.

2. Myths busted

There is probably no topic in human life where there is so much ignorance, myths and half-knowledge as in sex. We have put together four lists of 12 myths each. Can you bust them all?

3. Checklist

So how does consent actually look like? We have put together a list of possible signs (including moans and deep breahing- get thrilled) that help you to spot consent - and NON-consent. This will help you to understand your partner better.

(Secret hint from our team: this is a skill very much appreciated by all our sex partners!)

4. Resources

Want to learn more? Check out some of the amazing resources like the funny videos of Sex expert Laci Green and the most skillful introduction to what you need to know about vaginas from the guardian.

How do I get there?

To navigate to the course pages, just click on the headings on the left.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

3 What is consent?

Sexual consent can be best described as the active process of willingly and freely choosing to participate in sex of any kind with someone else. It also implies a shared responsibility for everyone engaging in, or willing to engage in, any kind of sexual interaction with someone else.

‘Willingly and freely choosing’ means, in this case, that we and our partners feel able to make and voice our choices, needs and preferences without being forced, manipulated, intentionally misled or pressured. Similarly, ‘participating’ means that we as well as our partners are seen and treated like a whole, separate person, not like a thing someone is doing things to.

Feeling worried? How does this affect consent?

(Illustration by Elyssa Rider)

American sex educator Jaclyn Friedman’s definition is also very helpful as it highlights that consent is a process rather than a one-off question. Friedman argues that

“sexual consent isn't like a light-switch, which can be either on or off. It's not like there was this one thing called sex you could consent to anyhow and all the time. ‘Sex’ is, instead, an evolving series of actions and interactions. You have to have the enthusiastic consent of your partners for all of them. And even if you have your partner's consent for a particular activity, you have to be prepared for it to change. Consent isn't a question. It's a state.”

In other words, as Friedman explains, consent is not something that can be demanded, expected or given and agreed once for all. On the contrary, it must be felt and mutually, clearly, enthusiastically affirmed. It is an open and active dialogue (as opposed to a lecture delivered by a single person) that we can all learn new ways to develop, and new ways to listen to.This course proposes ways in which we can become more attune to this dialogue. You can also find a list of some of the most pervasive myths and misconceptions that often surround sex and sexual consent.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

4 Myths busted I - ‘men are from Mars, women from Venus’...

1. A man who gets lot of sex is ‘cool’. A woman who gets lots of sex is ‘easy’.

Any self-defining man or woman (or person who doesn’t identify with either or just one gender) have the right to decide just how much, or little, sex they chose to engage in. Sex can be a lot of different things to different people: it can involve penetration, or no penetration, toys, words, physical contact….almost anything that two consenting adults want to engage in and feel comfortable with. However, these adults need to enter into that act on equal terms, with equal rights to safety, pleasure and enjoyment. Neither person should be judged differently. Sexual double standards or societal shaming of self-identifying women who engage in free sexual activity-still exist. It is up to us to challenge them and call them out.

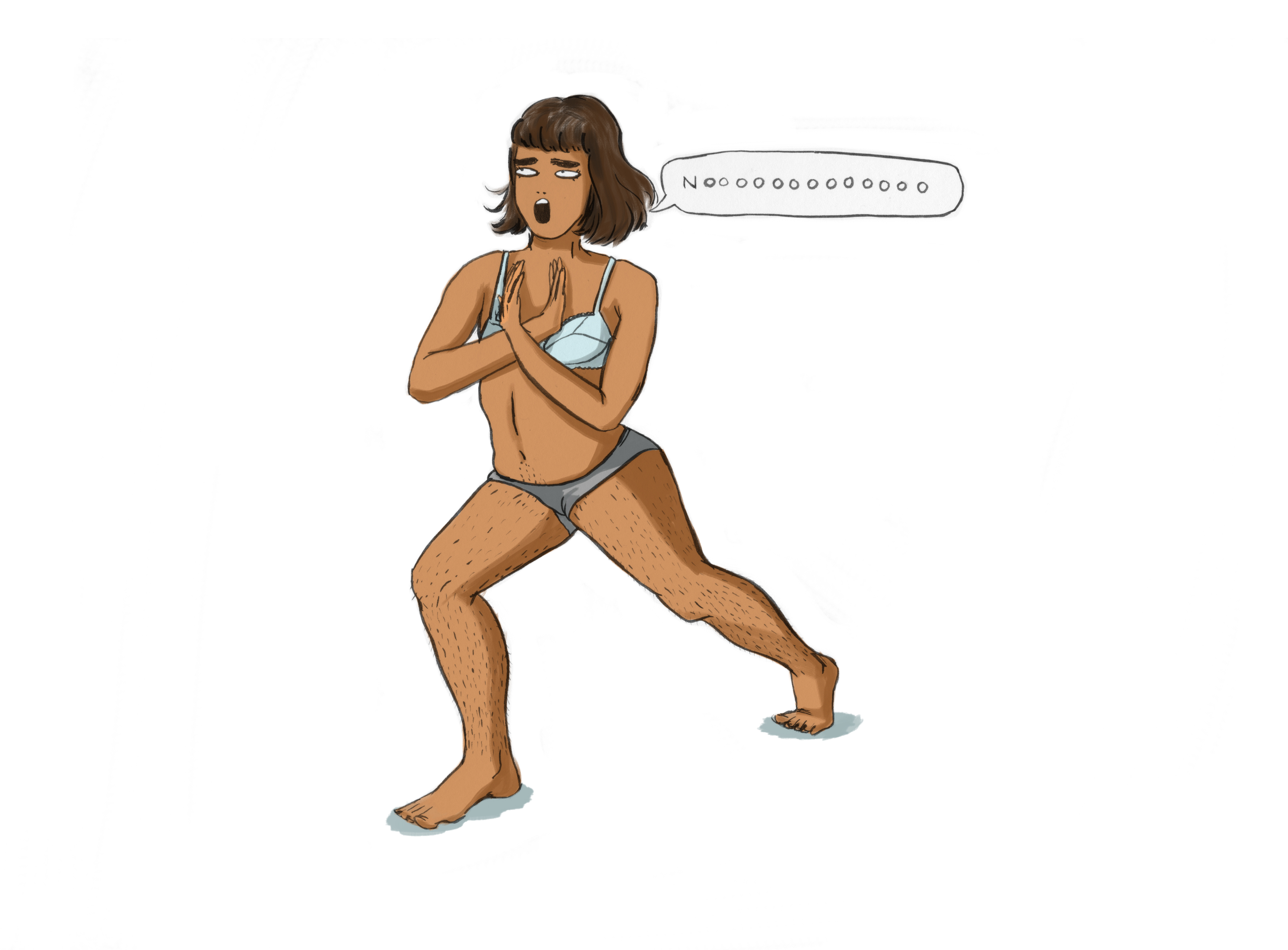

What do you think she means? No means no!

(Illustration by Elyssa Rider)

2. Women are naturally silent and submissive in bed. Men are naturally loud and dominant.

Luckily, everyone is different, and all desires vary depending on an individual (which makes the world a much more interesting place!). One cannot and should not make sweeping essentialist generalisations about gender (what a woman is, or what female sexuality is, or what a man is or ‘likes’). Moods and desires are not determined by arbitrarily assigned chromosomes. On the contrary, moods, desires, and preferences are cultivated over time and can change. We must be open to this possibility both when thinking about our own sexuality and that of our partners, however they identify themselves on the gender continuum.

3. Men only want sex. Women only want love.

Self-identifying men, women and any other individual not identifying with the gender binary (categorisation of human beings into males and females) want many different things at different times in their lives. Sex can be a wonderful way to express love, friendship and affection, but also be a pleasurable activity for people who are not involved romantically. However, respect, mutuality, consent and the well-being of all people involved need always to be ensured.

4. When a woman has sex with a man for the first time it will hurt: the hymen has to break, and that will cause the woman to bleed.

No! There is a popular misconception that the hymen breaks the first time a woman (or a person with a vagina) has sex, but hymens can vary an awful LOT. There are many different kinds of hymens, from imperforate hymens, which completely cover the vaginal opening and must be medically opened in order for the person to menstruate, to septate hymens, which feel like a strand of skin across the vaginal opening. Truth is, hymen usually doesn’t bleed. Any blood with first penetration is more likely due to general vaginal tearing from lack of lubrication.

5. A man always wants sex. There is something wrong if he does not. It’s his partner’s task to calm him down.

No matter how people identify (as men, women, non-binary, gender fluid or whatever else), there are multiple reasons why they may or may not want to engage in sexual activities. So much depends on their mood, physical and mental health, worries, previous experiences and traumas, attraction and feelings towards their partners. There are also people, including self-identifying men, whose sexual orientation falls under the so-called ace umbrella. These includes asexual, demi-sexual and gray-A people, who, with different nuances, do not, or do not often experience sexual attraction. Pressuring anyone who does not feel like having sex to conform to sexual expectations is harmful and disrespectful. At the same time, it is most natural for self-identifying women to experience strong sexual desire, and they should absolutely feel free to initiate sex if they feel comfortable doing it.

6. It is normal for women to experience pain in sex. There’s nothing really you can do about this.

In many cases, a self-identifying woman (or a person with a vagina) experiences painful sex if there is not sufficient vaginal lubrication (even though more serious medical conditions exist and can be discussed with medical professionals). When this occurs, the pain can be resolved if you are more relaxed, if the amount of foreplay is increased, or if you and your partner use a lubricant. There are also many self-identifying women who do not experience any pain, and women who may occasionally experience pain- it is very much dependent on your mood and psychological state.If you experience discomfort during sex you most definitely can take steps to act upon it. Do not be afraid to ask a partner to do something differently, to use a lubricant, or indeed, to just stop altogether. All of these things are ok and reasonable. Often partners are more relaxed and the sex gets better when they have talked about these issues.

7. Women do not masturbate. They do not experience sexual desire in the same way men do.

Self-identifying women, and well as individuals of any gender and sexual orientations, can most certainly masturbate and very often do. Women’s sexual desires have been historically portrayed as shameful, perverse or dangerous, with great damages on all of us. Masturbation is a great way to explore our bodies and sexuality and to understand our likes and dislikes, and entails by no means anything wrong, dirty or, say, unfair towards a partner. However, no one should ever feel obliged to masturbate and/or engage in any other sexual activities if they do not feel like it, or ever feel ‘abnormal’ because of it.

8. Heterosexual sex naturally ends with male ejaculation.

Certainly not! Sexual activities are a dialogue between consenting and enthusiastic people, and no one’s pleasure matters more than the other. Sex does absolutely not have to end with male ejaculation if the other partner does not want it to end. You should definitely not be afraid in setting claim to your sexual pleasure, or in communicating what you would like the partner who has just ejaculated to do.

9. It is shameful, or unmanly, for a man to express fears, dislikes, anxieties, traumas connected with sexuality and consent.

Self-identifying men, just like anyone else, have their own sexual history shaped by positive and negative experiences. It is a sign of strength and maturity from anyone to be able to share emotions and vulnerabilities. Unfortunately long-standing gender-based stereotypes shame and ridicule men for showing their more vulnerable side. Let’s not buy into this damaging narrative and allow ourselves, and all our partners, to be honest and truly present in an out of the bedroom!

10. Women tend to say no when they actually mean yes, or just need to be persuaded.

Certainly not (see all reflections above)! We get that consent is complex to understand and communicate: people may consent to sex as they feel pressured into it/ are scared of the consequences of rejecting their partners/ have been socialised into thinking that there is no alternative to something someone else imposes on them. It is important to be mindful of all these circumstances, and make sure we and our partners are freely and enthusiastically consenting to any sex we are engaging in. At the same time, whenever anyone is actually able to articulate a no, forcing them into whatever unwanted activity is wrong and harmful. This doesn’t mean you don’t have the right to ask your partners to discuss the reasons of their no or the emotional impact this had on you. Yet this needs to be done respectfully, and possibly with a cool mind: there is a huge difference between an honest conversation and trying to manipulate someone or making them feel guilty for asserting their boundaries!Gender stereotypes based on assumptions about what men and women should be, do or want harm everyone, and often do not allow people to express their true emotions and desires.

11. You can assume the kind of sex someone wants to engage in by what genitals they have.

Untrue - anyone of any gender and sexuality may have myriad reasons for not wanting to engage in certain kinds of sex. These reasons might relate to trauma, to pain or pleasure experiences, to gender identity (i.e. some trans people with penises may not want to use their penises for penetration in sex - some trans people with vaginas may not want their vaginas penetrated), etc. These and many others are reasons why it's important to communicate clearly and obtain consent for any form of sexual act, rather than assuming that someone consenting to a certain kind of sex means they consent to all kinds of sex.

12. Lesbian women never met a true man, who would have been able to change their minds. (aka: Sex with a woman doesn’t count, it’s basically just the foreplay without the sex).

Sex with women (or between self-identifying women) definitely does “count” in the way that heterosexual sex does. So long as two consenting adults are enjoying mutual pleasure it counts as sex. Sex does not exclusively refer to penetration, although self-identifying lesbians or bisexual people can engage in penetration (simply with their hands or with an ever evolving range of sex toys).Sex is not better or more legitimate when it takes place between a man and a woman. Sex is not simply penis in vagina penetration. It is many things to many people, and self-identifying women who have chosen to engage in consensual sexual relations with other women have made a personal life choice. Nobody should attempt to ‘change’ this.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

5 Myths busted II: Yes, that also counts as sexual violence

1. People can consent to sex when they are intoxicated, asleep, under the effect of drugs, in a situation of danger.

As someone cannot verbally or physically affirm their desire to take part in a sexual activity when they are not conscious they (logically) can’t consent. Even if they had consented earlier, or had consented a previous time, they cannot consent in that moment and therefore any sexual contact would be a crime.

2. When someone gets drunk and they are sexually assaulted, it was their fault.

See above. No. Instigating sexual contact, of any kind, with someone who is not able to consent is never ok (and generally illegal). Someone’s decision to get drunk does not change that fact. Alcohol consumption is legal in the United Kingdom, and in most European countries, for anyone over the age of 18, and people have the right to consume or not consume it as they see appropriate. Yet sexual assault and alcohol consumption are two very separate things: one does not negate the other, or excuse it, in anyway.

3. Touching people sexually without their permission, unwanted sexting, publishing their nude or sexual pictures or videos online is not abuse, it’s just banter.

Online abuse has sadly become increasingly common and has nothing to do with fun and innocent banter. It is a violent and vilifying act, and, legally, a crime. Survivors of cyber-abuse often struggle with long-term mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, self-loathing and suicidal thoughts. If ever you survived any of these experiences, you are incredibly brave and resilient, and support is available for you.

4. Men cannot be sexually abused.

Unfortunately, people of any gender and sexual orientation can be, and are assaulted and abused. The assumption that ‘true men do not get themselves raped’ is terribly harmful and makes the healing process of those self-identifying men who experienced sexual abuse even more challenging. Abuse is never the abused person’s fault, and gender-based stereotypes truly damage us all.

5. There is no abuse in LGBT+ relationships. Women cannot abuse each other.

Sadly sexual abuse can happen in many different context and self-identifying women can abuse as well as men (even though male violence on women currently counts for a great part of sexual assault cases). This means it is vital to understand and practice consent in any kind of relationship.

6. Assault only happens in dark streets at night. One can only be assaulted by strangers.

Most cases of assaults today happen in a domestic context, and the assaulter is someone the abused person knew. Too many survivors take years to realise that what they went through (for example, being forced into unwanted sex by an ex-partner) was a form of sexual abuse. Importantly, no abuse or assault is more or less serious or damaging than another, and all survivors need to be taken seriously and deserve the utmost support.

7. A sexual abuse that, for whatever reason, is not persecuted in a court is not real.

Sexual assault is a crime, and a serious one. However, some cases of sexual violence are difficult to persecute in court: perhaps because they happened a long time ago, the abuser was under-age, or evidence difficult to produce. The legal notion of assault varies from country to country, and some survivors also prefer not to go through the painful, and expensive, experience of a trial.

Again, they deserve everyone’s respect and support whatever their choice. While it is our duty to build a fair legal system and a healthy consent culture to tackle sexual violence in our society, we should remember that assaults that are not persecuted in the court are nonetheless real and profoundly traumatic experience. So are sexual encounters that may not qualify as assaults under a country’s legislation, but entail lack of consent from one side.

8. Sexual assault can be blamed on what the assaulted person was wearing.

Sexual violence has little to do with sexual attraction, and much to do with power and control. Men (or anyone, for that matter) cannot be ‘provoked’ or ‘lured’ into assaulting someone. People of every gender and sexual orientation, race and class get violated, in different times and spaces and independently of what they were wearing. This is a terrible truth we need to change by building a healthy culture of consent. Which starts by understanding that no abuse is EVER, on any account, the abused person’s fault.

9. If you bring someone back with you from a night out you’re giving them the green light for sex. If you make that decision you should deal with the consequences (aka: you can’t share a bed with someone and NOT have sex. That’s just impossible.).

We’ll repeat it again. And again. Sexual partners should consent freely to ANY activity they engage in. Going back home with someone, or sleeping in the same bed, does not mean we are consenting to sex, even if that person is our long-term romantic partner. And consenting to a certain sexual practice does not mean consenting to others, or that we’ll always do so. People ALWAYS have the right to say no, change their mind, and stop at any moment.

10. Sex in a relationship is never abusive.

Sadly even people who love us, or say they do, can harm us and violate our physical, sexual and emotional boundaries. Long-term partners, in the context of heterosexual as well as LGBT+ relationships, can be sexually abusive. This include forcing or pressuring their partners into any kind of unwanted sexual activities with themselves or others, and sharing sexual pictures or videos of them without their consent. Love never justifies violence or abuse, and, unfortunately, abusive partners tend to be recidivists (return to the abusive behavior multiple times). Many forms of support are available for those who wish to come out of abusive relationships, and techniques to learn to understand and communicate with our partners regarding our sexual and emotional needs can be learned (look at our piece on how to express/identify consent!).

11. Being sexually abused is shameful for the abused person.

Most emphatically not. Abusing, raping, assaulting is shameful and criminal behavior. On the contrary, surviving any of the above means you went through something terrible, but have been brave, resilient and strong enough to survive. Nothing of what happened to you was ever your fault.

12. It is OK to pressure LGBTQ+ people into heterosexual sex to ‘make them normal’.

There is a common misconception that peope’s sexual orientation can be changed or “normalised”, or that people can be ‘turned’ by sex. This is not the case. For many LGBTQ+ people, it can feel like everyone is expected to be straight. A 2012 survey by the Human Rights Campaign found that 92% of LGBTQ+ teens had heard negative things about being lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, and the pressures to conform to a certain set of heteronormative parameters undoubtedly feed into this uneasiness.

It is never ok to pressure anyone, regardless of their sexual orientation, into an act they are not comfortable with. And it is wrong to try and change someone who experiences desires or attractions that are completely normal and personal to them.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

6 Myths busted III: real sex, with real people, in real life

1. Sex in real life looks like sex in porn. There is something wrong if it does not. (aka. Sex in porn is a depiction of how good sex looks like)

Sex in real life takes a wide variety of forms, as human beings (luckily) are all different and very complex. Sexual activities can (and should) be pleasurable, enjoyable and mutually respectful, and may, sometimes, be awkward or emotionally challenging. However, they should never imply violence and/or lack of consent, in which case they fall under the category of sexual assault.Sadly many porns show violent, non-consensual sex, objectify women (treat them as objects for others’ gratification), and fetishise non-white and LGBT+ people. They also show bodies that are rather different from most of the viewers’ and often modified by cosmetic surgery, which tends to increase people’s insecurities. This doesn’t mean that there is anything wrong in stimulating sexual fantasies in ways that we find pleasurable. However, you may want to explore erotica and feminist porns, which try to be more respectful of women, LGBT+ and BME people generally bear in mind that your sexual life should not live up the expectations set by any director or actor.

2. Penetration is the only real sex. Forced penetration is the only real form of sexual abuse.

Let us emphasise this again: penetrative sex (penis in vagina) is by no means the only (acceptable) form of sex. People of any sexual and gender orientation can consent to and enjoy a wide range of sexual activities. Importantly, this also means that, apart from forced penetration, sexual violence and assault come in many other different forms. Forcing someone to unwanted oral or anal sex, touching, sexting or exposure to pornographic material are all examples of sexual assault. Cyber-abuse and revenge porn (sharing images or videos with nudity of sexual content without the explicit and freely given consent of all people involved) also counts as sexual violence. If you have ever gone through any of these traumatic experiences, please know that your pain is very real and you are not alone. Plenty of online and offline resources (peer support groups, counselling, rape crisis centres, self-help books, other forms of therapies etc.) are available for you. Never thing that what you underwent is not ‘bad’ or ‘serious’ enough to deserve love, healing and support.

3. It is OK, or even a compliment, to fetishise sexual partners (i.e. Hispanic women are naturally sexualised, Black people are wild in bed, Asian women are submissive, trans/bisexual people are promiscuous etc.).

Human beings have their own, complex individualities and all differ from one another. Some people may identify with cultural traits and even national stereotypes, but many feel extremely uncomfortable with being seen and judged through the lenses of their race, religion, origin or their sexual and gender orientation etc. When it comes to love and sex, we all wish to be wanted and desired for what we truly are, and treat someone as a fetish (an object that embodies a certain characteristic) is offensive and dehumanising.

4. Disabled people cannot have sex. Therefore, they cannot be abused (or they cannot have consensual sex without being abused).

People affected by physical as well as mental disabilities can most certainly explore their sexuality and engage, if they want, in sexual activities that vary a lot according to their condition, tastes, interests, sexual and gender orientations. Sadly many disable people, especially disable women, get also sexually abused, even in medical or therapeutic settings. However, this by no means imply that they cannot have a fulfilling and enjoyable sexual life based on enthusiastic and freely given consent.

5. All ‘normal’ people want sex (or a certain kind of sex) and experience sexual attraction.

Some people do not experience sexual attraction or experience it just at specific times and under specific circumstances, some others are happy to engage in romantic but not sexual relationships, and everyone is attracted to different people and/or enjoys different kinds of sexual activities. This is all completely OK, and no one should be forced or pressured to conform to someone else’s standards and expectations. Sometimes people, for example survivors of sexual assault of other forms of trauma, choose to abstain to sex for some time, and then they might ask for help and support while working on reclaiming their sexuality. In some cases, they might not. Every personal choice is always a valid choice.

6. Asking questions, setting boundaries, expressing needs and dislikes during sex makes it boring and unpleasant for a partner.

Far from it! Discussing what we want and like with our sexual partners can be a very sexy experience and, to many, a turn on. At the same time, those who feel they need to discuss their Dos and Don’ts in a less playful way, possibly out of the bedroom, are obviously in their full right. Above all, what makes sex enjoyable and exciting is people’s participation and involvement, which is likely to be way more enthusiastic and relaxed if everyone involved feels safe and respected.

7. Abused people are damaged goods. They never want sex (or always want it).

Abused people are courageous survivors and deserve all your respect. Some of them might struggle with some areas of their life, including sexuality. They might decide to take a break from sex to spend time on their recovery, or instead find that consensual sex is empowering and healing. All their choices are valid. If you are a survivor and struggle to make sexual choices that feel healthy and truly yours, please allow yourself plenty of time and forgive yourself for any set-backs. Psycho- or sex-therapy, as well as feminist and survivors-friendly erotica and self-help resources might help you reclaiming your sexuality (which does not necessarily entail having sex), in whatever way feels appropriate for you.

8. Once sex has started, it cannot be stopped.

Sex can always be stopped and everyone has the right to end a sexual act at any moment. Interruptions can lead to no physical consequences of any kind. It is important to communicate any discomfort or uncertainties to a partner, and to be receptive to any verbal or non-verbal signals that might indicate that a partner wants to stop a sexual act from happening.

9. Sex has winners and losers. It is about doing/giving something to someone.

Sex should be about shared fun and mutual enjoyment, relax, passion. Sadly in our society power dynamics are often at play, and women, non-binary people and historically discriminated against groups often (but not always) pay the highest price for this. It is important, however difficult, to dismantle all the beliefs and routines that bring us to think of sex in term of power. For example, self-identifying women (and no one else, for that matter) do not ‘lose’ virginity, and self-identifying men do not ‘win over’ their sexual partners. Of course, sex implies sometimes assertive communication and negotiation, asserting boundaries and so on. But it must always take place in the context of mutually respectful relationship between equal, consenting adults. This applies to BDSM and ‘kink’ practices (in which the exploration of power relationships can be explored but is always carefully negotiated) as well as to the most ‘vanilla’ of sexual encounters.

If you are a survivor of any form of abuse or trauma you might especially struggle with reshaping your beliefs about sex: allow yourself time and plenty of care, you deserve it.

10. Being sexually rejected by a partner is shameful. Your sexuality defines your self-worth. (aka. She didn’t want to sleep with you in the end? You loser!”)

Rejection, as and in itself, is not shameful. Rejection of any form, in any area of life, can feel upsetting, or frustrating. But it is essential to accept that people have the right to say no to us, as we can to them. The word rejection is also problematic: a partner saying no to sex does not mean they are rejecting you. It means they are exercising a freedom of choice, and (for various reasons) may not want to engage in a certain activity, at that moment in time.

Similarly, sexuality does not define your self-worth. Self-worth comes from all the different things that make a person an individual. Your talents, achievements and attributes stretch way beyond your sex life, and whilst it is important to feel proud and happy about your sexual choices and preferences, it is by no means the only (or in any way the most important) thing that defines you. It is important to remember that both in and out of sexual scenarios.

11. Bisexual people are just indecisive, you are either gay or straight. Sexuality and desire are fixed and always stay the same.

Sexual preferences are not set in stone and can change over time, often depending on the immediate situation the individual is in. This is often described as Sexual Fluidity. For example, if someone identifies as heterosexual, they might at some point in their life feel increased sexual or romantic attraction to same-gender persons. Like any other social trait, sexual preferences, attitudes, behaviours and identity can be flexible to some degree. Bisexuality is defined as the romantic or sexual attraction to two or more genders/same or different genders. If you ask people who identify as straight, but then have sex with someone else of the same gender, this experience does not necessarily make them “bisexual”, but it might well make them sexually fluid.

12. It is OK (or even our right) to talk to others about our sexual partners and the sex we engaged with them without their permission.

Sex is by no accounts shameful, but is an important, delicate and private part of our life. No one has the right to share intimate details’ about someone else’s sexuality without their permission. In particular, the assumption that ‘boys will be boys’ and that self-identifying men are justified in indulging in this kind of ‘lock-room banter’ is damaging and sexist. It harms those partners who had not consented to have their sexual lives discussed by others, and all those self-identifying men who feel obliged by social expectations to join in kind of conversations they might feel uncomfortable with.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

7 Myths busted IV: yes, no, maybe … consent in your sex life

1. The lack of a no means yes. Maybe also means yes.

Consent needs to be continuous, enthusiastic, clearly and freely given. The lack of a no, or of a clean-cut no, are definitely not enough. It is of course difficult to learn to vocalise consent and recognize verbal and non-verbal signs in others (which is why we provide you with a non-exhaustive but useful list of examples). However, this does never justify violating other people’s boundaries. Also, consent is sexy: questions about our and our partners’ likes, dislikes and desires can make sex more fun for everyone involved!

2. When someone said yes once, or to a specific sexual activity, they said yes to all and always will.

Consent is a state rather than a pledge or a choice for life, and can be withdrawn in any moment. People can change their mind, and feel like engaging in one specific activity and not in another. Everyone has the right to set specific boundaries and should never feel pressured, criticised or ridiculed for this. Please make sure that you and your partners are always mutually checking on each other’s well-being!

3. When someone experiences an erection or vaginal arousal, they are always consenting to sex.

No, for multiple reasons. A partner might be consenting to a certain sexual act but not necessarily a type of sex (e.g. penetrative or oral). A partner might be aroused in that moment but not feel the same level of arousal later (hence the importance of communicating), or the arousal may be involuntary. One cannot know whether a partner who is physically aroused is consenting to sex unless you you ask or check explicitly! It is also important to know that some survivors of sexual violence experience physical arousal during the assault, which they still live as an insufferable violation of their bodies and minds. Physical arousal has nothing to do with consent and one person’s actual desire to engage in sex.

4. When someone had sex with other partners, it is safe to assume they will do the same with others.

No, not at all. Sex differs from partner to partner and from scenario to scenario. You cannot assume that, just because someone has done something once, they will want to repeat that experience. Also, desires and needs change with time and circumstances. Sometimes people want to have sex and sometimes they don’t. This is why it is always important to ask a partner what they feel comfortable doing, or to make sure that they are giving affirmative signs.

5. Consent is simple: yes means yes and no means no, even when there are strong power differences (i.e. age\class\wealth differences, between a student and a teacher, an employer and employee etc.).

Consent, like many things in life, is far from simple. Sometimes people are able to clearly articulate a no, which we must respect in all cases. Some other times, however, someone might feel pressured or manipulated into sex because of the power dynamics between them and their partners. These include strong differences in age (even when all people involved are underage), or when one of the partners is in a position of authority (a teacher, an employer, a sport coach, a priest). In this last cases, sexual encounters actually tend to be illegal.

6. It is OK to pressure a partner to have sex without contraception. Sex with no contraception equal trust, or ‘sex with love’.

Contraception is about protecting ourselves and our partners from STDs (sexually transmittable diseases) and/or unwanted pregnancies. It is equally important in LGBTQ+ sexual encounters and/or sexual activities where there is no, or little risk of pregnancy. People make different choices about contraception, and this often changes in the context of long-terms relationships in which partners know each other well, have been tested for STDs etc. This does NOT mean that contraception is no more necessary, but simply that other options may be available (for example, contraceptive pills or implants instead of condoms). However, no one should ever disrespect their partners’ choices and force or manipulate them into anything. Far from expressing trust and love, this is an act of control and abuse.

7. We owe sex to a loving partner (or one we have been with for long enough).

Not at all. Sex is a personal choice and should never be imposed. We do not owe anyone sex, and a loving partner will understand any decisions we make, or factors that might influence our decision to not have sex, or to prefer one type of act over another.

8. It’s OK to bite, slap, scratch or spank someone during sex without checking first.

These actions have the potential to cause pain and physical scarring. Whilst people can derive pleasure from this, and many do choose to practice BDSM related activities (which vary in form and intensity), these are things that must be clarified with and agreed upon with a partner. It is unfair to impose preferences or acts on a person without their consent. If you think you might want to experiment with biting, slapping etc. please make sure your partner is comfortable with it first, and discuss any limits (or uncertainties) that a person may have. Also, if ever you feel pressured to engage in any unwanted activity and are not sure of how to set and express your boundaries, techniques for assertive communication can be learned!

9. Consent is all about the body. Consent is all about the mind.

This is an interesting one. Sometimes we think we really want to have sex, and then our body seems to disagree with us (for example, when erection or vaginal arousal prove to be difficult). Some other times our bodies react to stimulation, but intellectually and emotionally we feel we do not want to be sexual (and if sex is forced on us, this can make it a case of abuse). It is very useful to learn to pay attention to the messages our body sends us (which can be done, for example, through practices such as yoga, mindful, breathing exercises etc.), as well as to stay in tune with our emotions. Ideally, in fact, we want to consent to sex with all our mind and body. Of course, there is absolutely nothing wrong in trying to get more aroused (for instance, using lube) if having sex is what we truly want. Similarly, it happens sometimes that physical stimulation does actually put us in the right mood and mindset for sex. However, no one should ever impose on us any of these options.

10. Adults who are already experienced do not need to worry about consent.

Every sexual act must involve two consenting adults, and the age and degrees of experience of the people involved do not change that. Consent should be a given- experienced adults, or people who have been sexually active for a long time, are no different.

11. Discussing consent is not appropriate for religious people.

Consent is crucial to anyone, even those who choose not to engage in sex. Of course no one should be forced in conversations they do not want to have about their sexual lives. However, religious people most certainly can learn to understand and express their boundaries, communicate and recognize consent and have frank and honest discussions on these matters if they wish to.

12. Monogamous people, people who have already been tested for STDs, and queer people who engage in sex with no risk of getting pregnant do not need to worry about consent.

Again, consent concerns us all. It encompasses issues of contraception, and how we can protect ourselves and others from STDs and unwanted pregnancies. But is also, most importantly, refers to what we really want from our sexual life and every sexual encounter we experience, and how to articulate it and communicate it to others. Everyone needs to be mindful of consent matters.

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

8 Do the test! Consent checklist

We have put together a fairly comprehensive, but non-exhaustive, list of verbal and non-verbal ways which can help you spotting that consent is being given. We have been inspired by the tables used by the great sex educators from American website Scarleteen, but have also added some suggestions of our own.

When looking at the examples here below, please remember that consent is not a fixed, or permanent state. It is always subject to change, and can vary from person to person. Never be afraid to ask, or (conversely) to state what it is that you like and don’t like. Sex should always be a dialogue and not a lecture, between participants who have just as much right to explore their preferences in a safe manner.

1. To begin, let’s think of some ways we can ask about consent (or establish it):

Can I [do whatever sexual thing]?

I’d like to [do whatever sexual thing]: is that ok? No? Would you perhaps like to do anything else instead?

How do you feel about doing [whatever sexual thing]?

Are there things you know you don’t want to do? What are they? Mine are [whatever they are].

Is there anything you’d like us to do so you feel comfortable or safe doing [whatever sexual thing]?

I'm really interested in doing [whatever sexual thing] with you, and it feels like the right time for me: does that feel right with you too?

Do you want to do or try anything new/different when we’re together?

2. How to not establish consent

The following type of questions, instead, do NOT establish consent, and can mean that the person you are with has not properly understood what active consent means. If someone says any of the following to you, you should NEVER feel pressured to say yes or agree.

Let's do [whatever sexual thing.]

I want [whatever sexual thing].

You really liked it when I [whatever it was you did before], I’ll do it now.

I heard guys/girls really like it when someone [does whatever], so let's do that.

Let's just do it: I'll take care of you. You're okay, right? You trust me, don’t you?

3. Here are some examples of what verbal expressions of consent, as well as non-consent, can look and sound like:

Possible verbal signs of consent | Possible verbal signs of NON-consent | |

|---|---|---|

yes | no | |

yes | maybe | |

definitively / I'm really sure | I am not sure | |

I know | I don't know | |

I'm excited / turned on | I'm scared / this isn't turning me on | |

Don't stop! | stop | |

Yes! / heavy breathing / moans | [silence] | |

More! | no more | |

I want to. | I want to, but | |

I feel really good | Wait, I feel worried about… | |

I want you / it / that | I don't want you / it / that | |

Touch me there | Not there | |

I still want to | I thought I wanted, but… | |

That feels amazing / nice | That hurts | |

Mmmmmmm. | [silence] | |

I love this | I love you/this, but | |

I want to do this right now, like this | I want to do this, but not right now/this way | |

I'm ready | I'm not sure I'm ready | |

Keep doing this | I don't want to do this anymore | |

[insert praise to your deity of choice here] | [no such praise] | |

This feels so right | This feels wrong | |

YES! | [silence] | |

I like it this way! | Please, not like this | |

4. Here are some examples of how non-verbal expressions of consent and NON-consent, can look and sound like

However, please bear in mind that consent needs to be enthusiastic and clearly given and, we’ll repeat it again, can be withdrawn at every moment. This means that while a partner might be enthusiastically consenting to something and express this in one of the ways summarised here below, they may not necessarily agree to another sexual activity.

At the same time, please pay attention to the non-verbal signs of non-consent, and, if ever spot any of them, check whether your partners feel safe and at ease.

Possible non-verbal signs of consent | Possible non-verbal signs of NON-consent |

|---|---|

Direct eye contact | Avoiding eye contact |

Initiating sexual activity | not initiating any sexual activity |

Pulling someone closer | pusing someone away |

guiding someone's hand to be touched in a certain place or way | Avoiding touch |

Nodding yes | Shaking head no |

Feeling comfortable being naked (or ways of being vulnerable sexually) | Discomfort with nudity (or being otherwise vulnerable sexually) |

Laughter and/or smiling (upturned mouth) | Crying and/or looking sad or fearful (clenched or downturned mouth) |

"Open", relaxed body language, like loose and legs, relaxed facial expressions, turning towards someone | "Closed" body language: tense, stiff or closed arms and legs, tight or tense facial expressions, turning away from someone |

Sounds of enjoyment, like an enthusiastic moan, heavy breathing | Silence or sounds of fear or sadness or whimpering or a trembling voice |

Changing positions, responding physically to touch | "Just lying there" |

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

9 Resources on consent

Sex education (all you wanted to know towards a more fullfilling and mutually respectful sex life):

Resources for survivors of sexual violence:

Great sex ed videos:

Vagina, vulva, clitoris - Do you know where to go?

Vagina Dispatches from theguardian. com

Great sex educator Laci Green, talking about STDs, hymen, G-spot

Consent education, projects & ideas:

National Union of Students (NUS) offer great materials for trainers and teachers:

Wonderful workbook of a sexual consent workshop elaborated by the University of Bristol:

Sex health glossaries:

This course has been created by GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, in cooperation with Serlo.

10 Well done! One last word before you go...

Congratulations for finishing the sex education course on consent!

One last word:

Together with the wonderful team of GenPol, a think-tank on gender and politics based at the University of Cambridge, Serlo is establishing a database with courses, vidoes and other materials on sex education.

If you liked this course, please do like us on facebook (which will increase our likelihood to be found by others and to get funding).

If you are passionate about sex ed, why don't you join us? We are a diverse group of different gender, sexual orientation, nationality etc. We are sure your skills and ideas will enrich our team. If you are interested or have any other questions, please do not hesitate to contact us!

You can also leave your comment in the section below. We value your feedback to improve our course!